Bangkok Utopia: Modern Architecture and Buddhist Felicities, 1910-1973 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2021)

My current book-length research project investigates the sometimes-competing and sometimes-complementary images of utopia that developed in the Thai capital, Bangkok from 1910 until 1973. Expressed in built forms as well as architectural drawings, building manuals, novels, poetry, and ecclesiastical murals, these images of an ideal society attempted to reconcile urban-based understandings of Buddhist felicities such as Nibbana, Uttarakuru, and Phra Sri Ari with worldly models of political community.[1] Using Thai- and Chinese-language archival sources, this book-length study demonstrates how these strivings to create an ideal society made common cause with the interests of the monarchy, the marketplace, and the military to produce new opportunities for both social play and political conflict in urban space.

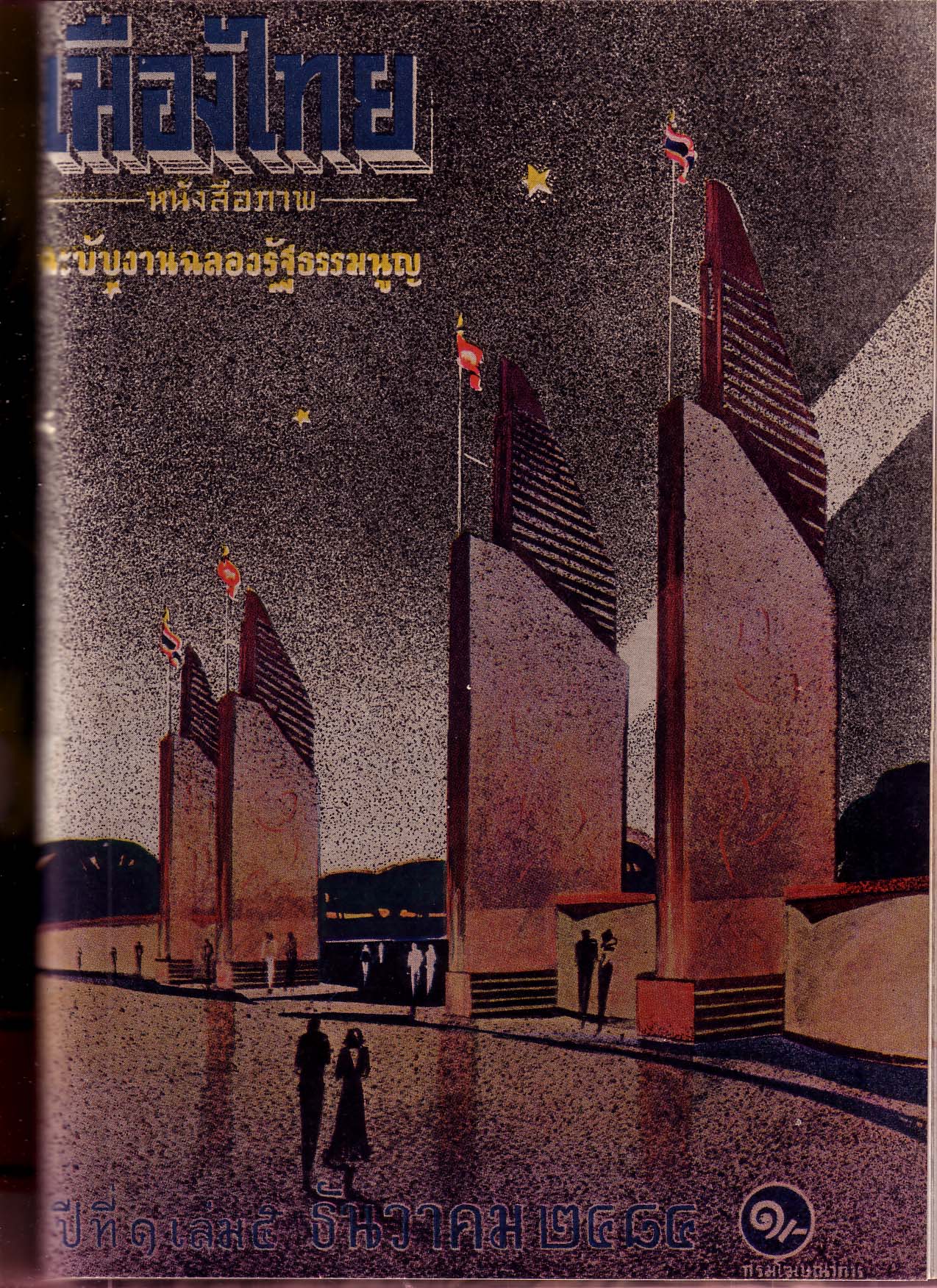

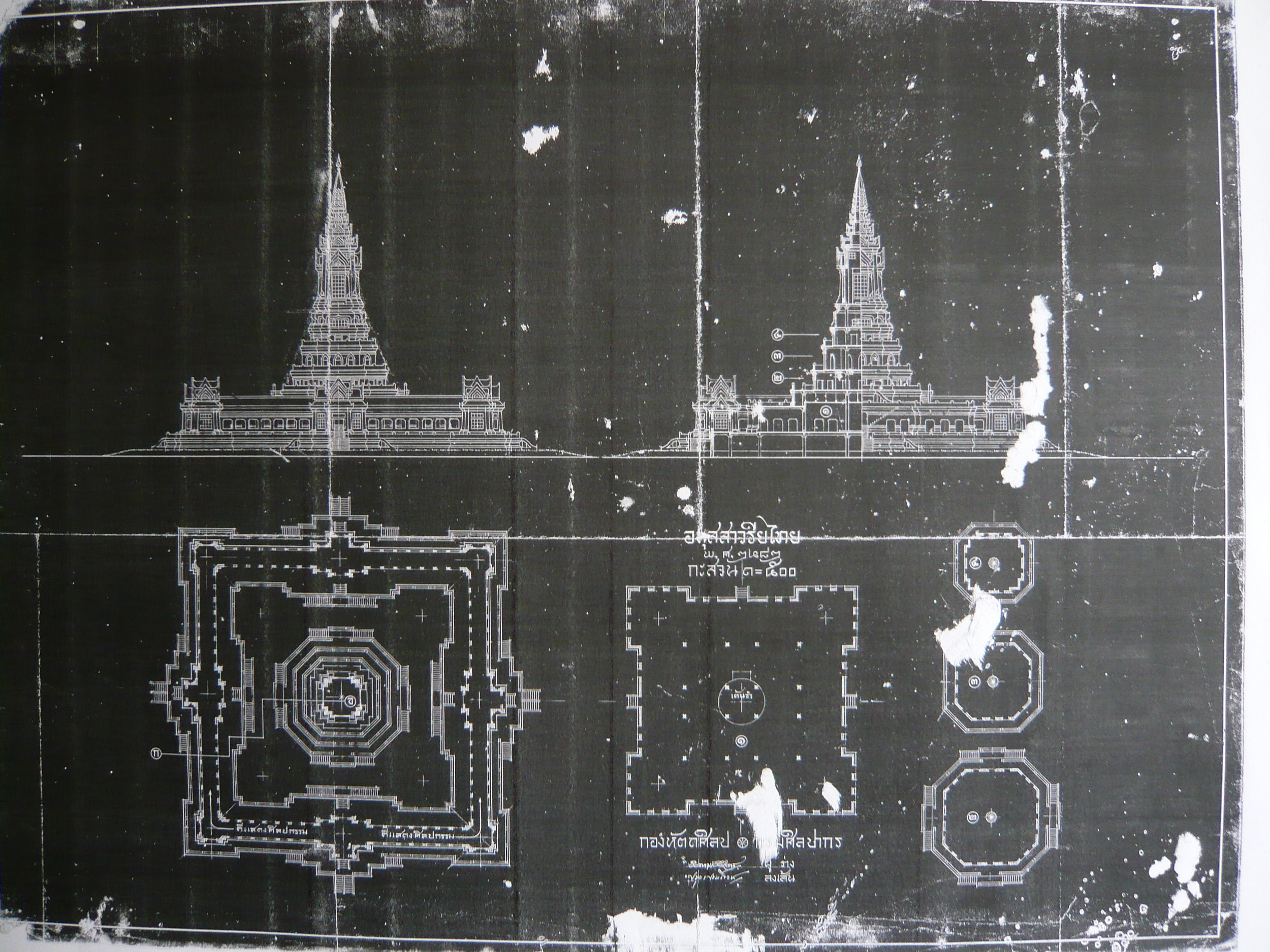

From the miniature democratic city built by Siam’s last fully reigning absolute monarch in 1917 until the installation of a national infrastructural network of roads and hotels in the 1970s, changes in the Buddhist spatial imagination re-shaped the city’s urban fabric and produced new models of political community.[2] The city was no longer presented as the center of a pre-ordained sacred geography, but was imagined as a designed cosmography produced by human labor. While the geometries of the mandala governed the organization of the town, the palace, and the wat or monastic complex in 18th-century Siam, 20th-century Bangkok expanded to incorporate new symbolic centers of political power as well as modern arenas of public assembly like the cinema and the stadium. Built and un-built utopian projects developed in the Thai capital that reconfigured the relationship between the Siamese ruling class and its subjects by reconciling modern architecture’s rationalist tendencies with older cosmologies.

The interplay of Buddhist culture, modern economic, political, and social change, and speculative thinking about the future can be traced back to the beginnings of print capitalism in 19th-century Bangkok but by the 20th century, thinking about the past, present, and future of Bangkok society came to be expressed in distinctly spatial terms.[3] Reflecting both top-down approaches to urban planning and bottom-up responses to urban conditions, these utopian models were embedded within three interrelated historical developments in Bangkok’s polyglot society and economy. The first was the change in the spatial imagination brought about by the transition from mandala polity to nation-state that placed the capital at the center of a new geo-body.[4] The second was the reorganization of the building trades and the transition from craftsman to architect as chief purveyor of built works. The third was the change in social relations between the monarchy and the diverse peoples it ruled over. Together these events produced a form of nationalism that re-imagined the bonds between the Siamese ruling class and its subjects as participants in a shared utopian project.

Utopian nationalism was part of a broader cultural and economic campaign on the part of the Siamese monarchy to assert their relevance in a turbulent urban landscape transformed by extraterritorial laws, migrant Chinese labor, and the rise of new urban classes. The old economic and political machinery of the state was rendered obsolete by the integration of Siam into the world capitalist economy, but a new system had not yet fully developed to replace it. In reaching back to an imagined past as well as projecting into a modern future, utopian nationalism filled this caesura, allowing the old regime to revive itself, albeit in an adjusted form.[5] By examining the ways that the new spaces of the city became arenas for modern subject-formation, utopian desire, political hegemony, and social unrest, this study outlines a theory of the modern city as a space of antinomy, able to sustain not only heterogeneous temporalities but also support conflicting world views within the urban landscape. Underscoring the paradoxical character of utopias and their formal, programmatic, and narrative expressions of both hope and hegemony, Bangkok Utopia provides a new way to conceptualize the uneven economic development and fractured political conditions of contemporary global cities like Bangkok.

A chapter from this project appears as "A Tale of Two Crematoria: Funeral Architecture and the Politics of Representation in Mid-Twentieth-Century Bangkok," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 77:3 (September 2018)

[1] I use the term after Steve Collins, who describes Buddhist felicities as “forms of salvation” and includes heavens, earthly paradise, Metteyya’s millennium, the Perfect Moral Commonwealth of a Good King. Steve Collins, Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 110.

[2] The currently reigning dynasty was founded in 1782 in Bangkok. The country they ruled over was known as Siam before the name of the country was officially changed to Thailand in 1939.

[3] Early Thai-language newspapers published Buddhist jataka tales alongside news of the outside world and invited readers to submit “solutions” to hypothetical “problems” from everyday life. See, Sudara Seriwat, Wiwathanakam khong ruang san nai muang thai tangtae raek jon pho so 2475 (“Evolution of Thai Short Stories from the Beginning until 1932CE”) (Bangkok: Ministry of Education, 1977).

[4] The mandala polity is a conceptualization of an arena full of petty kingdoms rather than a centralized state. This plan reflected a network of loyalties between ruler and rules and among rule, all of whom aspire to be the highest lord of the area over which they claimed sovereignty, Sunait Chutintaranond, “Mandala, Segmentary State and Politics of Centralization in Medieval Ayudhya,” Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 78.1, p. 90. OW Wolters, History, Culture and Religion Southeast Asian Perspectives, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1982, p. 25. The geo-body of a nation refers not only to its territory but to the image of the territory that is recognizable to its citizens, Thongchai Winichakul, Siam Mapped: A History of a Geo-Body of a Nation (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1994).

[5]In the mid-19th century, as the old system collapsed and merchant capitalism expanded in Siam, the power of local lords or khunnang decreased because they remained tied to old production relations. The monarchy, on the other hand, benefitted from capitalism, allowing the Siamese state to centralize and, in turn, establish royal absolutism. Jit Phumisak, “Chomna khong sakdina thai nai patchuban,” (“The Real Face of Thai Feudalism Today”), Nitisat 2500 chabap rap sattawatmai (“The Faculty of Law Yearbook 2500 to Greet the New Century”), (Bangkok: Thammasat University Faculty of Law, 2007); Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch, Feudal Society, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), vol. 1, pp. 170-173, 189; Seksan Prasertkul, “The Transformation of the Thai State and Economic Change, (1855-1945),” PhD dissertation, 1989, pp. 453-459.